Blisters vs. Bottles: Examining Prescription Packaging

More often than not, here in America our pills are no frills.

Unlike Europeans, the U.S. consumer is accustomed to seeing most medications packaged in bottles. In fact, an estimated 80% of all prescriptions in the U.S. are dispensed in bottles, with about 20% packaged in blisters. By contrast, about 85% of oral solid dose products in the European market are packaged in blisters, which are known to provide heightened individual pill protection, barrier properties, and adherence options.

Let’s take a step back to appreciate how odd this is. In a world interconnected by international commerce, the vast majority of consumable products – especially those in developed economies with cultural similarities – are quite similar. We buy beverages in cans and cartons, bread in flexible plastic wrap, sauces in jars. And when we go to the doctor, everything from bandages to booster shots have largely uniform packages and delivery devices.

Why, then, are the predominant oral solid dose packaging formats so drastically different on each side of the Atlantic? There’s no simple answer, but legacy manufacturing equipment is certainly a key factor.

Far less ambiguous, though, is this easily supported statement: blisters offer many advantages over bottles. And those advantages are growing in a changing global marketplace.

For years, it’s been recognized that blisters offer various benefits to manufacturers, pharmacy staff and patients. These include – but are by no means limited to – child safety, product quality, medication adherence, and patient outcomes.

More recently, though, another argument for blisters has emerged, one coinciding with the packaging sector’s biggest buzzword: sustainability. For starters, if you thought those amber vials you toss in a curbside recycle bin are actually getting recycled… well, keep reading.

What follows is a comparison of blisters and bottles across a variety of critical factors, concluding with a discussion about advancements in materials science that have the potential to revolutionize eco-friendliness in pharma packaging.

Child-Safety: Required by Regulations, A Responsible Strategy

Enacted in 1970, the Poison Prevention Packaging Act (PPPA) requires most medicine to be in special packaging. “Special packaging” is defined as being designed or constructed to be significantly difficult for children under 5 years of age to open within a reasonable amount of time, while also not being difficult for adults to use properly. The PPPA and related regulations are codified at: 16 CFR Subchapter E (parts 1700 to 1702).

Studies have consistently shown that blister packaging outperforms child-resistant (CR) bottles. In March 2018, CBS News reported on a study citing “Blisters are 65% more effective in preventing child access to medication.”

The segment went on to report that young children can open “child-resistant” pill bottles in seconds, risking accidental poisoning. In a test the group set up at a Maryland day care center, children ranging in age from 3 to 5 managed to pop open child-resistant pill bottles in mere seconds.

In 2015, child poisoning from access to medications was reported in 8,972 cases in the United States. Much of this is undoubtedly due to the drawbacks of bottle design; when caps are inadvertently left off or only partially closed, the CR feature is obviously rendered moot, leaving all of the pills exposed to a child. By contrast, blister packs require each pill to be accessed separately, and can therefore provide significantly higher levels of child safety. Some blister solutions achieve a child-resistant safety level of F=1, the highest rating available.

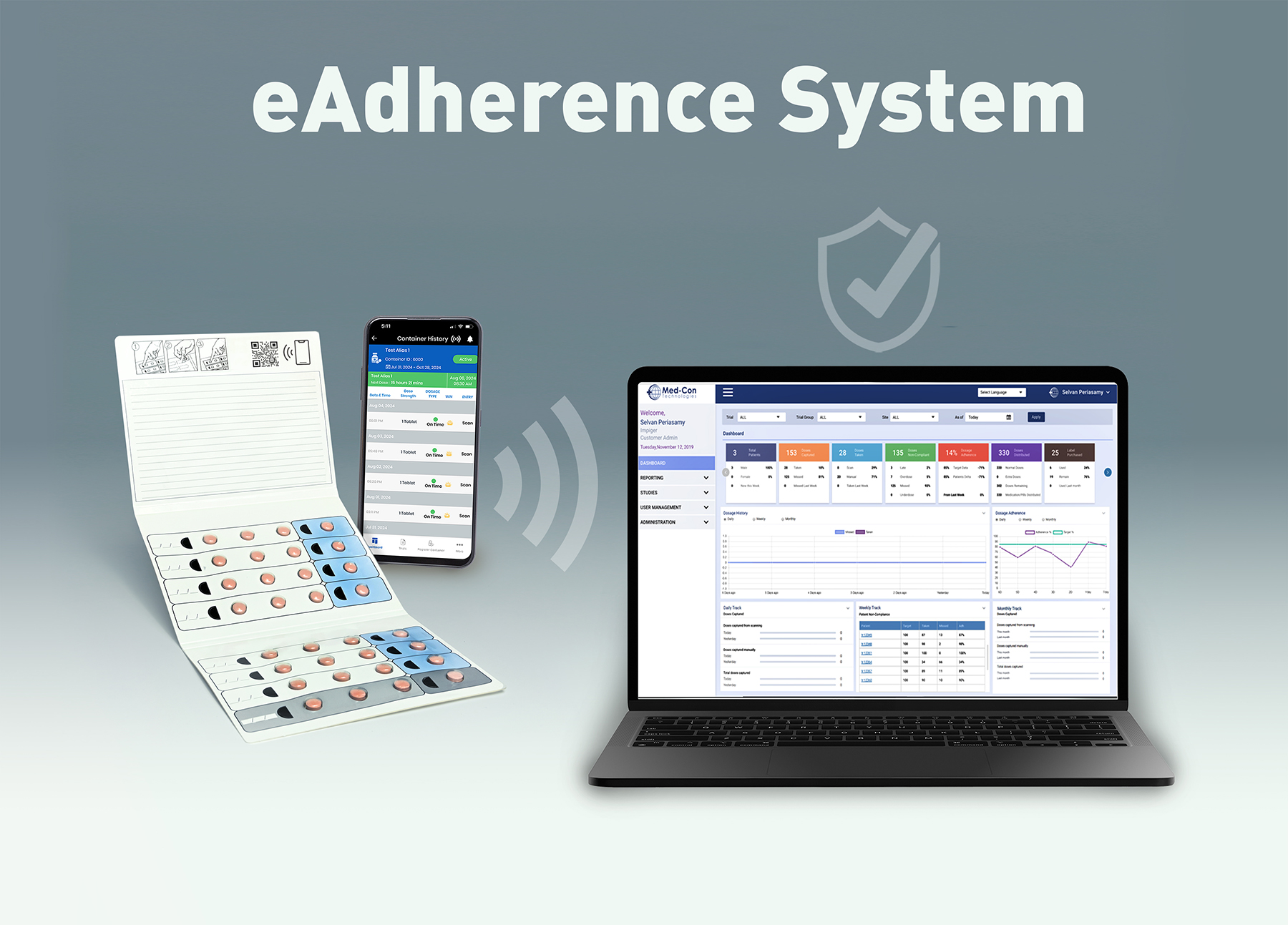

Medication Adherence: The Influence of Packaging

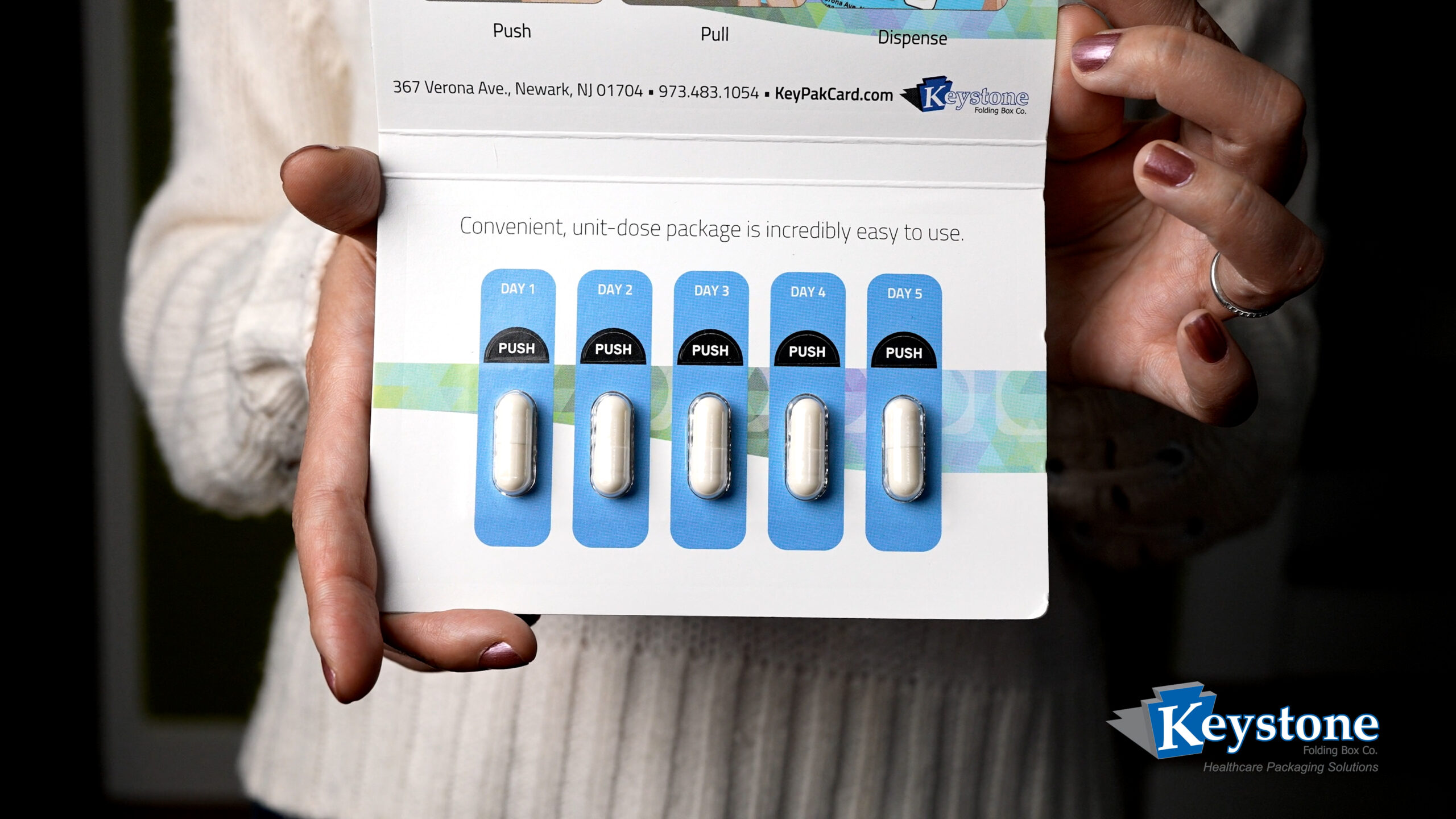

Published studies have shown a direct connection between calendarized blister packaging and improved patient compliance, a.k.a. adherence to dosing regimens. While medication adherence is a complex issue, calendarized blister packs directly counteract patient forgetfulness by providing a visual dose history for each day of the week.

- Improved Adherence: Unit-of-use blistered medications are easier to use, particularly for patients taking multiple pills per dose and those who have difficulty remembering proper dosage protocols. By adding printed dosing instructions on the pack near each dose, the packaging becomes a dose-prompting “reminder package,” directly impacting insight into dosing history. Beyond the dosing direction from physicians and pharmacy staff, the package is something the patient interacts with on a daily basis, making it a repetitive communication device with the patient regarding proper dosing. The oral contraceptive market is an example of how “compliance packaging” works; in fact, not a single birth control pill is sold in any other packaging format. Conversely, a bottle offers no benefit in the area of improving adherence.

- More accurate dispensing: Pre-packaged medication in blister packs reduces the chance for dispensing errors in pharmacy settings. Medication in prepackaged unitof- use blisters allow prescriptions to be filled faster and more accurately, since no error-prone pill counting and repackaging by pharmacy staff is required. If a mistake has been made by a pharmacy staff member when pulling a drug from the shelf, both the name of the drug and the strength of the medication remain visible to the patient, allowing the patient an opportunity to verify they have received the correct product. On the other hand, when prescriptions are dispensed in bottles, the patient has nothing on which to rely other than the pharmacy label and the hope that they have received the correct medication.

- Improved refill rates: Blister packages make it easier for patients to manage their own supply of products. With bottles, many patients don’t realize they need to refill their prescription until they are down to the last one or two pills – a “too little too late” scenario that can lead to missed doses until the patient can procure a refill. In stark contrast, the expanded real estate offered on a blister package means helpful prompts such as “time to refill” can be printed near the last few doses in the package – a friendly reminder to call in for a prescription refill.

Product Quality: When “Good Enough” Isn’t Good Enough

Every medication package, both bottle and blister, must go through stability testing to ensure an adequate barrier of product protection is provided. The goal is to protect the medication from moisture and/or oxygen, either of which could negatively impact a product’s chemical assay and reduce efficacy.

With a blister package, each pill cavity protects the dose inside until it is removed, assumedly for consumption immediately or shortly thereafter. This approach best ensures optimal product quality.

Bottles can be deceiving when it comes to product quality. For example, when a manufacturer packages product in a 500-count bottle, there is stability data that allows that product to have the necessary barrier protection until the initial opening of the bottle. Once the cap is removed (and induction seal broken) to fill the first prescription, the barrier is never the same. Each time the bottle is opened to fill yet another prescription, the ambient air and humidity of the room is introduced to the remaining product inside. Of course, pills sent home with a patient in a traditional amber vial only compound bottles’ barrier protection conundrum.

The result of a 2015 study published by the Healthcare Compliance Packaging Council (HCPC) points to degradation risks associated with plastic bottles. The study supports concerns pertaining to exposure to moisture and oxygen, and the associated impact on medications – even under normal usage conditions. The results also showcase how the composition of tablet packaging can determine the medication’s likelihood of degrading. Specifically, polypropylene vials, highdensity polyethylene (HDPE) bottles and polyvinyl chloride (PVC) blisters, all of which are found in traditional retail and institutional pharmacy settings, may increase tablets’ risk for higher physical degradation when compared to highbarrier single-dose packages such as PVC/Aclar® or PVC/ polyvinylidene chloride (PVdC) blisters.

The study concludes that U.S. patients taking medications from non-barrier packaging may not get the intended clinical benefit of the drug due to potential product degradation from daily exposure to the home environment.

Stemming from the study, Walter Berghahn, Executive Director of the HCPC, remarked: “Packages need to protect pharmaceutical products during their entire life cycle. As shown in this study, single-dose packages using high-barrier materials can accomplish that goal so long as the temperature profile is maintained. Once we move closer to protecting these products appropriately, we help ensure that patients receive effective products.”

Environmental Impact & Sustainability: Reduce, Reuse, Recycle

And that brings us back to the recycling bin. Or rather, what many of us think happens at the local recycling center.

According to a 2017 article in National Geographic, “A Whopping 91% of Plastic Isn’t Recycled.” This includes a significant amount of medication packaging made from plastic resin.

Are amber vials recyclable? It might appear so. Flip it over – see that number with the chasing arrows circling it? That’s the corresponding recycling stream. Most amber vials are polypropylene (PP), so it’s usually the number “5” debossed on the bottom.

The issue isn’t that #5 plastic can’t be recycled. It’s simply that polypropylene is not recycled – because the vast majority of recycling centers in the United States screen out polypropylene products. In fact, less than 30% of Americans have access to recycling systems that accept polypropylene.

Type of plastic aside, another issue with all bottles is that size does indeed matter. According to the Association of Plastic Recyclers (APR), “Items smaller than two inches in two dimensions render the package non-recyclable… The industry standard screen size loses materials less than two inches to a non-plastics stream… or directly to [landfill] waste.” In other words, amber vials’ small size is why U.S. landfills are filling with a sea of tiny orange containers with prescription labels on them. This applies to plastic bottles made from HDPE as well.

But blister packages aren’t recyclable either, right? While historically that’s indeed been the case; the amount of plastic in a blister package is exponentially less than that in an amber vial. So, if we assume the likelihood that neither will be recycled, the blister packages are less environmentally damaging because they beat bottles on one of sustainability’s three R’s: Reduce. In some cases, a switch from bottles to blisters can reduce the amount of plastic going to landfill by 80%. Less plastics equals more eco-friendliness; that equation has been true for decades. And recently, an additional factor has shifted the math even further toward blister packs.

The recent introduction of recyclable blister materials made from high density polyethylene (HDPE) presents incredible potential for drug manufactures and large retail pharmacies to reduce plastic landfill waste. Several prominent films suppliers have shown both the barrier viability and comprehensive recyclability of these next-generation films used to produce blister packaging. This seems revolutionarily right now; in five years it will be commonplace.

Thus far, though, recyclable blister constructions alone have faced a crucial challenge: child-resistance. Simply put, it’s difficult to make a blister with a high-level CR feature both effective and recyclable. It’s a materials science hurdle that hasn’t been solved.

However, by pairing a recyclable blister with a secondary paperboard carton with F=1 child-resistance (again, that’s the highest-possible CR rating), a truly sustainable medication package can improve the way we deliver both OTC and prescription drugs to the market. When finished with the package, the consumer simply separates the paperboard card from the blister component and recycles each.

Where Do We Go From Here?

While many organizations may feel they are limited to the use of bottles due to their current equipment infrastructure, there are many contract packaging organizations well equipped to take on the task of packaging or repackaging medication in blisters. These contract packagers can allow for a rapid change in packaging format. Large retail pharmacies have successfully purchased drug in bulk from either manufacturers or wholesalers and had contract packagers manage the process of repackaging into unit-of-use blisters.

For the past 50 years, eighty percent of U.S. pharmaceutical products have been packaged in the same plastic bottle format. Novel blister packaging designs present opportunities to have a meaningful impact on child safety, patient adherence, product quality and the commitments many companies have made to sustainability and the future of our environment.

About the Author: Ward Smith is Director of Marketing & Business Development for Keystone Folding Box Co., a manufacturer of folding cartons and compliance packaging for the healthcare sector. The company is best known for its Key-Pak and Ecoslide-RX blister cards, each of which are child-resistant (F=1), senior-friendly and made from recyclable material. www.keyboxco.com ward.smith@keyboxco.com.