Blisters of Mercy

Child exposure to pharmaceutical substances appears to be decreasing, but what more can packaging companies do to push the trend?

US-based Keystone Folding Box serves the packaging needs of pharmaceutical and healthcare manufacturers from the busy port of Newark, New Jersey. Having grown up in a family of pharmacists, Director of Marketing and Business Development Ward Smith shares the same passion for innovation and service as those involved directly with the medicine making process. Both his father and grandfather owned and operated independent pharmacies, where Smith worked from a young age before earning a degree in communication studies at Florida State University. From there, Smith was recruited into the packaging industry, where – due to a series of positions with escalating responsibility and more than 3,000 packaging projects – he has found a way to continue the legacy set down by his pharmacist grandfather.

“I can safely say that every product’s packaging requirements are unique,” Smith says. “At the same time, there are certainly similarities that could be adopted, transferred, or modified in some way.”

Here, Smith shares how pharma packaging specialists are a vital part of the supply chain and how his own problem solving skills help improve product quality and patient outcomes.

What do you find most rewarding about packaging for the pharma industry?

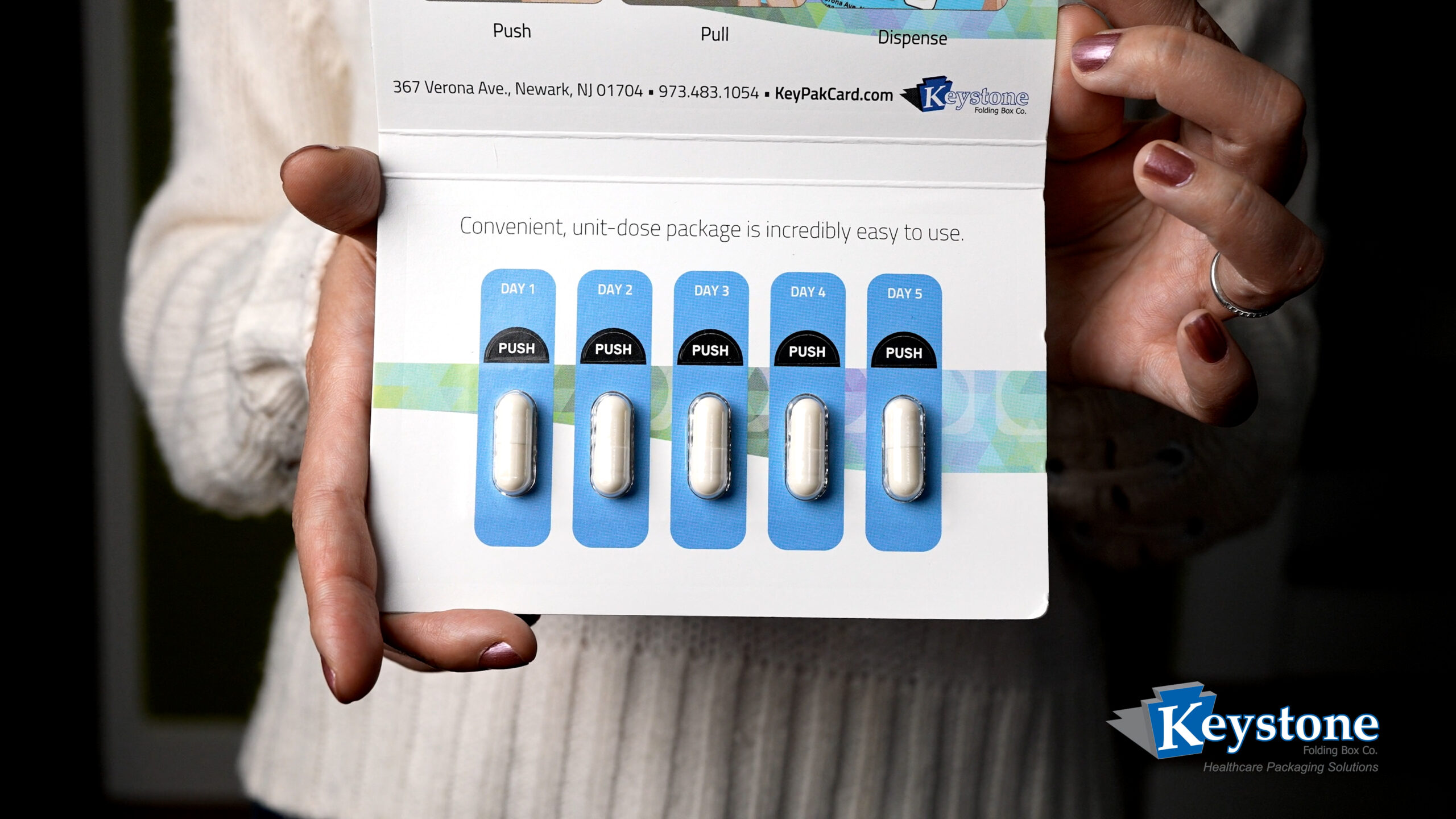

Our large pharmaceutical client base is always challenging us to create unique packaging solutions, but one of my most satisfying professional experiences has been the award of a co-patent for a reclosable, eco-friendly, child-resistant paperboard pack for blister packaged products. Over 250 million of these are now in use by a leading national pharmacy retailer. Developing packaging innovations that have real-world application is a key part of what we do. An idea must “hit on all cylinders” to become a commercial reality. Unless a package enhances patient health and makes sense operationally, economically, and sustainably, it’s little more than just a neat idea.

What are the important standards when it comes to child-resistant packaging?

The standards have not really changed in recent years, but it is important to make the distinction between what is child-proof and what is child-resistant. When designing packaging for pharmaceutical products, we follow the guidelines outlined in the Poison Prevention Packaging Act1970, as well as the related regulations (codified at: 16 CFR Subchapter E (parts 1700 to 1702)).

Child-resistant or ‘‘special packaging’’ is designed or constructed to be significantly difficult for small children to open or for them to obtain a toxic or harmful amount of the substance, but not difficult for adults to use. Child-proof packaging cannot be opened by small children at all.

Has there been a distinct and quantifiable reduction in child harm since the introduction of safety packaging?

A report published in 2021 conducted a retrospective analysis of the 2009 to 2019 National Poison Data System (NPDS) annual reports to examine trends in US poison exposures and related fatalities in children. The findings signal an overall linear decreasing trend in childhood poison exposure to pharmaceutical products. During the study period, children in age groups of 0–5 and 6–12 years experienced an overall decrease in poison exposures. In summary, from 2009 to 2019, the annual number of reported poison exposures in US children decreased significantly.

Looking at the increase in use of child-resistant blister packages, we believe the rate of reduction is due, in part, to a growing use of blister packages. Consider that when caps are inadvertently left partially closed or off the bottles, the child-resistant feature becomes irrelevant. In contrast, blister packs can provide a significantly higher level of safety for children. Some blister solutions can provide a child-resistant safety level of F=1 – the highest child-resistance rating available.

Can you explain exactly how blister packs improve safety?

If a child is able to remove a bottle cap, the child has access to all the contents in a single moment. Blister packs require extra effort and time to remove each pill, significantly slowing down the child’s access. By adding a child-resistant feature to the blister package, children have an even lower chance of accessing a single dose, much less multiple doses.

Do government agencies need to improve existing safety standards?

Tragically, there has been an increase in deaths of children who are exposed to poisoning by opioids. To help combat the ongoing opioid epidemic in the US, the FDA and the Institute for Safe Medication Practices are encouraging changes to product packaging that help to deter abuse. This specifically includes promoting the use of limited doses dispensed in blister packs.

In 2018, a bill, known as the SUPPORT Act, was passed into law that allows the FDA to require special packaging for such drugs, including customizable fixed-quantity blister packaging for opioids and other drugs that pose a risk of abuse or overdose. The FDA is currently seeking feedback on potential use of this new authority to require that certain immediate-release opioid analgesics be made available in fixed-quantity, unit-of-use blister packaging. To date, the FDA has not issued guidance, nor has it in any way forced drug manufacturers to adhere to required packaging changes.

Are child-resistant caps/closures or blister packs safer?

In terms of safety, studies have consistently shown that blister packaging outperforms child-resistant bottles. In a March 2018 broadcast, CBS News reported on a study citing “Blisters are 65 percent more effective in preventing child access to medication.” The report further states that kids can open child-resistant pill bottles in seconds, risking accidental poisoning. In a test that the group set up at a Maryland day care center, children aged 3–5 managed to pop open child-resistant pill bottles in mere seconds.

How is Keystone factoring in wider trends such as sustainability and the circular economy?

Types of plastic aside, another issue with all bottles is that size does indeed matter. According to the Association of Plastic Recyclers (APR), “Items smaller than two inches in two dimensions render the package non-recyclable […] The industry standard screen size loses materials less than two inches to a non-plastics stream […] or directly to [landfill] waste.” In other words, amber vials’ small size is why US landfills are filling up with tiny amber containers – with prescription labels still attached. This applies to high-density polyethylene (HDPE) bottles too.

But blister packages aren’t recyclable either, right? The materials used to form the blister are typically PVC- or aluminum-based, which render the product non-recyclable. Historically, that has indeed been the case because the amount of plastic in a blister package is exponentially less than that in an amber vial. So, if we assume the likelihood that neither will be recycled, blister packages are less environmentally damaging because they beat bottles on one of sustainability’s three Rs: “reduce.” In some cases, a switch from bottles to blisters can reduce the amount of plastic going to landfill by 80 percent. Fewer plastics equals more eco-friendliness – an equation that has been accepted as true for decades.

Recently, an additional factor – the introduction of recyclable blister materials made from HDPE – has shifted the math even further toward blister packs. HDPE presents incredible potential for drug manufactures and large retail pharmacies to further reduce plastic landfill waste. Several prominent films suppliers have shown both the barrier viability and comprehensive recyclability of these next-generation films to produce blister packaging. This seems revolutionarily right now, but in five years it will be commonplace.

Thus far, however, recyclable blister constructions alone have faced a crucial challenge: child-resistance. Simply put, it’s difficult to make a blister with a high-level feature both effective and recyclable. It’s a materials science hurdle that hasn’t yet been solved. However, by pairing a recyclable blister with a secondary paperboard carton with F=1 child-resistance, a truly sustainable medication package can improve the way we deliver both OTC and prescription drugs to the market. When finished with the package, the consumer simply separates the paperboard card from the blister component and recycles each.